One call away

Villani and Fukushima volunteer at the Community Helpline

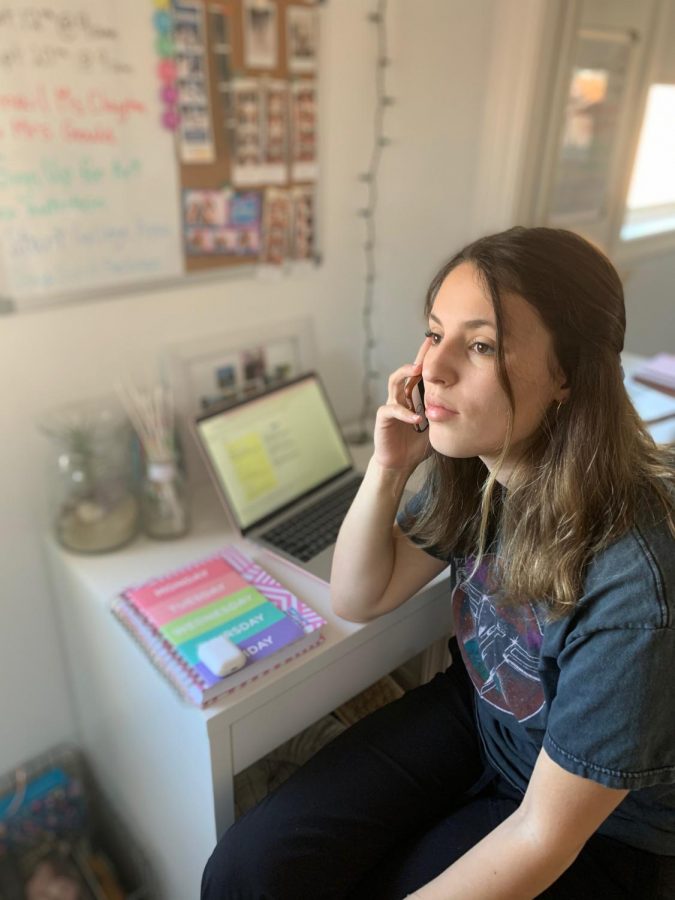

Senior Katie Villani talks on the phone with a caller from the Community Helpline, where she has volunteered for over a year. PHOTO COURTESY OF KATIE VILLANI.

Since 1971, the Community Helpline has come to the rescue for many people wrestling overwhelming emotions burdensome, distressing emotions and a wide variety of disorders nationwide. Seniors Katie Villani and Ella Fukushima are just a couple of the students at RUHS who have trained, contributed volunteering hours and mentored together to act as a support system for those that rely on the helpline.

According to Villani and Fukushima, the purpose of the helpline is to offer a space for people struggling with mental disorders to discuss their feelings openly for free. Many of the callers call multiple times and are called “repeat callers.” Callers mostly consist of adults. The listeners practice actively listening to the callers, but are unauthorized to give medical advice.

“They need someone to talk to because most of the callers don’t have that social or emotional support system. Instead, they call the helpline to have an anonymous, unbiased listener to almost rant or vent out how they’re feeling,” Fukushima said.

Villani and Fukushima discovered this opportunity in AP Psychology when fliers were given out by teachers to encourage high schoolers to volunteer.

According to Villani and Fukushima, the “passion” and “interest” they have for a career in psychology prompted them to volunteer. While Villani is still deciding whether she wants to pursue psychology, Fukushima plans to have an “emphasis” in counseling psychology.

“One of my biggest strengths is my passion in psychology. Because I love doing this and I love helping others, this community service opportunity just fits perfectly for me,” Fukushima said.

People call the helpline to talk to an anonymous, unbiased listener to vent out how they’re feeling.

— Ella Fukushima, senior

The application process consisted of making a resume and an over the phone interview. Applicants have to be 16 years or older to be able to volunteer. However, there are a variety of volunteers extending from high schoolers to college students, parents and other adults.

For two months, there were one hour lectures twice a week covering topics such as domestic violence, substance abuse, suicide, OCD, schizophrenia and more. To get comfortable with responding to calls, volunteers practiced their skills in role-play situations. Mentors are there to aid starters for their first couple calls.

“My first call on my own ever was a suicide call. That was extremely stressful. At the end of that call, it went from the topic of suicide to us laughing over our favorite movie. Just hearing someone have a genuine laugh, I felt very happy that that person was able to take their mind off of suicide and start to get out of that dark place,” Fukushima said.

Due to COVID-19, precautionary measures forced the Community Helpline to transition shifts to home. The Ooma Office App, used to send calls directly from the office to their phones, and the iCarol website are used to log in information about the callers. Between March and June, Fukushima claimed there was a peak in callers.

“A lot of callers were overwhelmed by this idea of having to stay home. So, they called a lot more frequently than before because there’s this whole new added stress and overwhelmingness that was bothering them,” Fukushima said.

Work shifts are usually picked based on a listener’s schedule. Typically, they work two days a week for three hours. Both Villani and Fukushima agree that “it’s not super time consuming” and doesn’t interfere too much with their schedules.

Now that they’ve participated in the helpline for over a year, and are accustomed to the protocols, they can monitor and mentor trainees; this position is called a facilitator.

“You facilitate roleplays, and teach [trainees] better things to say than what they were saying before. When you start mentoring, they watch you take calls, and you watch them take calls. You tell them what they’re doing right and wrong, and lead them through,” Villani said.

This method of active listening, using verbal nods like ‘mhms’ and ‘yeahs,’ that are “instilled” into the listeners, has earned the Community Helpline praise and recognition for being a distinct helpline from others, according to Fukushima.

“A lot of people have said on the lines that we’re the only helpline that isn’t asking really invasive questions, and that we just listen. A lot of times, people who call suicide hotline or 2-1-1, will get transferred to our line if they’re not in immediate emergency and are about to hurt themselves or someone else to just talk,” Villani said.

According to Villani and Fukushima, interacting with people over the phone and forming closeness and trust within the helpline has gained them many close bonds with callers.

“There’s this one caller, where her relationship with her daughter was not good at all. They did not want to talk to each other all. They talk to each other everyday now. Their entire family dynamic has changed, and I think that’s one of the coolest things that she can be like, ‘Ella! My daughter called me today!,’ and I can just be like, ‘I’m so happy and proud for her!’ That’s one of the best things ever,” Fukushima said.

Relationships aren’t just built with the callers though. The community of listeners, according to Fukushima, is filled with very “sweet” and “amazing” people.

“I’ve made some pretty good friends. I’ve gotten closer to people from RUHS who do it. I’ve also met lots of people from PV, Torrance high schools, some from Costa and even some of the adults. You just talk to anyone there,” Villani said.

For both students, volunteering at the Community helpline has made them “grow” and has improved their “empathy and understanding for others,” Fukushima said.

“You’re not a person’s therapist, but you’re listening to them, you’re listening to their problems and you’re understanding what people go through,” Villani said. “You realize a lot of people go through worse things than you realize. It’s really eye-opening.”

Heyy I'm Simra and this is my fourth year on staff. Aside from Journalism, I love walks on the beach, reading, and Netflix. I'm a big advocate for bridging the gender gap in STEM. I am also interested...