No A’s for effort

The P.E grading scale is unfairly skewed among students

The RUHS physical education grading scale is simple. For the fitness run, eight laps is an A, and the rest follow in succession: seven is a B, six is a C, five is a D and four is an F.

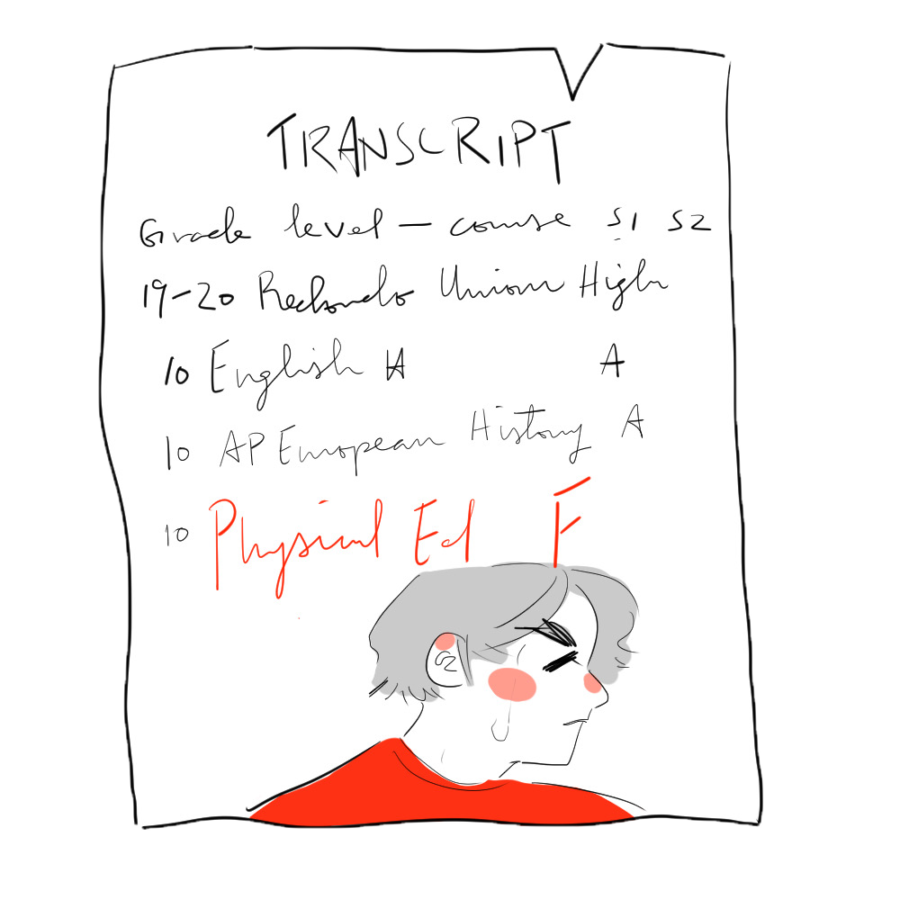

In my high school career, spanning the three years between freshman year to junior year, I have only received three B’s. The first one was for health, where I took all the tests in one week. The next was for a semester of chemistry due to the fact that I was miserably failing to calculate joule values. The last one, most shamefully, was in PE because I could not run anything over six laps during the fitness run.

I still remember it vividly: a field of tomato-faced freshmen nursing their bottles of sun-warmed water, the timer shrieking like it held a grudge against mankind and my PE teacher’s disappointed eyes as I said my assigned number, held onto my knees and dripped sweat onto his shoes.

My intention isn’t to recount my humiliation at the hands of the AstroTurf or all the precious electrolytes I lost to my teacher’s sneakers, but to point out a pattern I noticed in not only myself, but also in the people around me: the grading scale, based on skill rather than effort, seems to be discouraging students.

There are some obvious flaws with this particular grading policy, such as physically strong students having the leg up on their less athletically inclined peers, heavier students having to work harder because of their higher body weights and the genuine shame that teens feel towards their inability to reach a certain marker of health and the teaching of potentially unhealthy fitness ideals that don’t respect each individual’s unique body types. There’s another flaw, however, that is much more odious: the constant negative feedback that skill-based grading hands to the students that need encouragement the most.

Commonly tossed around as buzzwords in dog training programs, parenting guidebooks and certain elementary school classrooms, the concept of negative versus positive reinforcement is forcefully emerging within popular culture. It’s broadly accepted that positive reinforcement is typically more effective and long term—so why is it that our PE grading scale still demonstrates a model of negative reinforcement?

One of the earliest studies of the effects of negative reinforcement involved shocking a rat until it learned to pull a lever that stopped all the shocks immediately.

The current grading scale functions somewhat similarly to this: the student is dropped onto the field and has to suffer by running in circles until they reach the desired amount of laps, at which they are allowed to end their running and lay on the field. Students who cannot meet the required amount of laps are forced to continue running, and their grades decrease with each lap they miss. PE asks you to exercise, meaning that the student, like the poor rat who can never find the lever, must also undergo physical discomfort until the authority ends the experiment.

Also, like the rat, there seems to be some unspeakable element of psychological torture here. While it has been found that negative reinforcement initially works better than positive reinforcement, it eventually stops working and builds resentment—on the track, you would see this in the form of students gradually getting slower and slower until they would only walk two laps, accepting the inevitable F.

So what can we do to decrease frustrated, disengaged students and increase PE’s overall enjoyability?

We could shift more towards an effort-based grading scale; adjusting the percentages of how much those runs count would provide great relief to weaklings like me.

Perhaps the world is not ready for a PE that goes beyond running laps and teaches better eating, yoga, stretches, proper form, and a sustainable relationship with fitness. Perhaps the world is not ready for a PE that encourages and praises each student and asks them to take responsibility for their own health.

But RUHS may be ready for an effort-based scale that would encourage students to do the wiggling and jumping and running that their bodies need them to do without the stress and humiliation that has traditionally been attached to PE.

Hi, I'm a first time senior and a second time entertainment editor. When I'm not scurrying about to meet deadline, I work as a cat butler -- it's not much, but it pays the (kitty) bills.