Reporting out

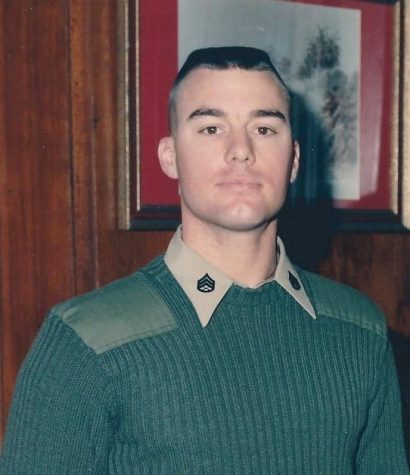

Chief Warrant Officer 3 Willoughby leaves RUHS after 13 years as Senior Marine Instructor

As a teacher, he’s watched students grow up from freshmen to seniors who eventually graduated to continue the next chapter of their lives.

This time, he’ll be the one leaving.

For thirteen years, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Keith Willoughby (retired) has taught the Marine Corps Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps (MCJROTC) program at RUHS as the Senior Marine Instructor (SMI).

The 2019-2020 school year was his last year teaching at RUHS.

“It was just really a blessing to be able to come home and have an influence on the youth in the area where I grew up,” Willougby said. “It helped me to kind of stay young. When you’re dealing with young people all day, you’ve got to have that youthful mindset, you can’t be an old badger stuck in your ways, you have to still be flexible and adjust accordingly to different situations.”

Before teaching MCJROTC, he spent 20 years in the Marine Corps, which he joined mostly because his friend didn’t think he could do it.

“I joined the Marines because a younger friend of mine who graduated high school early decided to join the Marines, and he asked me to come down and visit him on visitor’s day, down in San Diego. And when I did, I was impressed with what changes I saw in him, and after our conversation was almost done, he laid it out for me. He said it was really hard, but ‘I wouldn’t recommend it for you because you couldn’t handle it.’ So that was like, ‘Oh, let’s go,’” Willoughby said. “I went to the recruiter’s office the next day.”

His dad, who was former Navy, was concerned as to why Willoughby wanted to join the Marine Corps, so they talked over coffee. Willoughby told him, “Why would I join the rest when I could be the best?” Soon after graduating high school, Willoughby shipped off to boot camp, which he attended at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego and graduated from in August 1981.

“Boot camp was interesting. Basically, the first day that we got our drill instructors, they were asking us questions and we’re all yelling and stuff, and one of the drill instructors comes over to me and tells me, ‘Are you afraid of anything?’ and I said ‘No, sir.’ So he decided to make me the platoon guide, the leader of all the recruits. That worked for a couple of weeks,” Willoughby said.

As the guide, Willoughby led the recruits and carried a guidon, which is a flag that marks the unit. Since he was positioned in front of everybody else in formation, he had no reference as to how far away he was from the other recruits.

He lost this position a couple weeks in.

“We’re out drilling one day, and the guide is in the front with the guidon, and the drill instructor is calling cadence and we’re doing different commands. The drill instructor’s voice just kept getting more faint and more faint because I’ve got no reference, I’m the guide, there was nobody to refer to. So finally he calls ‘platoon halt’, and he says ‘Willoughby!’ I turn around and I’m way away from the platoon. I’ve done marched off on my own,” Willoughby said. “So he gets mad at me and fires me from being the guide, and makes me the squad leader.”

As an “eighteen-year-old punk kid,” he copped an attitude by shuffling and stomping with the unit instead of marching, which subsequently led to him getting fired from being a squad leader, and sent to the back of the unit.

However the consequences of his attitude didn’t stop there.

“Every day from there on out, virtually every time we came back to where we lived, it was called the squad bay, I had to go on the quarter deck and get thrashed,” Willoughby said. “Mountain climbers, bends and thrusts, until I was sweating every day. I hated it, but it also made me strong as an ox.”

Due to the intensity of boot camp, there wasn’t any time to make friends, but afterward when he went to Military Occupational Specialty school (MOS), he roomed with a man named Bernhardt. They had the same graduation date and often ran into each other when they were stationed at the same places, causing them to become good friends over a long period of time.

After MOS, he went into postal and became a mailman for the Marine Corps, an experience he considers to be rewarding.

“When it comes to people in the military, especially when you’re in a combat area, there’s three things you don’t mess with: you don’t mess with people’s chow, you don’t mess with their pay, and you don’t mess with their mail. This is back before the times of cell phones and emails, so you’re getting a letter from your mom, dad, girlfriend from home. You’re getting a care package from home, whatever some kind of communication from the real world. Those letters are important,” Willoughby said.

During the Cuban Migrant Crisis, thousands of Cuban refugees were fleeing to the United States in order to escape rioting in Cuba. They were detained in Guantanamo Bay with no way to communicate to their families in the United States.

“So the military postal service agency called Camp Lejeune and said, ‘We need to send one of your officers down there to Guantanamo Bay to set up a post office so these people can communicate with their families.’ Because I spoke Spanish and it was my records, they chose me, so I got to go down and do a joint task force operation in Guantanamo Bay to support these Cubans in the encampments,” Willoughby said. “That was six months long, and I was awarded the Joint Service Commendation Medal for my service there.”

Continuing to work in postal, he was stationed at the Marine Corps air station El Toro for one year, and Iwakuni, Japan for one year, working as a clerk in both places. Then he was stationed in Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, where he worked as a postmaster.

“When I was a young Marine, I was at El Toro, and I was a dirtbag, I really was. So much so that there was one point where my mom had the opportunity to come in and meet my warrant officer that was in charge of me in postal. The warrant officer told her specifically, ‘Your son needs to do his three years and get out of the Marine Corps. He’s not Marine Corps quality,’” Willoughby said. “I was kind of that way for a while until a couple things happened “

The first thing that changed him was when he got in trouble during a big inspection, and he had to stand for inspection every day for two weeks until there wasn’t a single discrepancy. Then, in Iwakuni, he became good friends with Bernhardt, who was a positive influence on him. According to Willoughby, “he helped me become a better Marine.”

After being stationed in Iwakuni and going to Noncommissed Officer school there, he was selected to go to a drill instructor school in Camp Lejeune, where the expectation to complete every assignment perfectly in a limited amount of time was “incredible.”

He was required to memorize an entire drill manual and be able to carry out any movement that was asked of him, run PT and give classes. He also had to wear the uniform “to the point of razor sharp creases in your uniform, no sit down creases, your shoes perfectly shined, clean, not a speck of dust on them, your ranks perfectly placed. Everything perfect, perfect, perfect.”

“I felt very accomplished [for finishing drill instructor school]. I felt very proud of what I had done. But I also felt the weight of the responsibility now that’s on me. Now I’ve got to go out there and train young men to become Marines and potentially go to war for our country, so it was rewarding yet challenging at the same time,” Willoughby said.

As a drill instructor, he trained 18-19 year old recruits on Parris Island. For three months, the recruits were away from their families as they became Marines.

“We get to graduation day and they get dismissed. I’m standing in front of them, and their families are fifty feet behind me. They could just run past me, because they’re done, they’ve been dismissed. They can leave if they want,” Willoughby said. “But they don’t. They come to me first. And they shake my hand and they say, ‘Thank you, sir. You made me into a man.’ It lets you know that the hours and hours and hours of hard work that you put in were worth it. You made a difference in these people’s lives.”

Near the end of his military career, he was stationed in the San Francisco Bay area and later set up a one man detachment in Carson. Soon after that, he retired on Nov. 1, 2001. The transition from Marine to civilian life was smooth, since he already worked on a civilian base where there were few military personnel.

“We go back to the command in the Francisco Bay area and see all the people I had worked with for the previous four years. It’s kind of like a homecoming in that respect. And then my parents were also there, and I liked to see how proud my dad was of me for completing twenty years in the Marines and retiring, so that was a really neat day,” Willoughby said.

After retiring from the Marine Corps, he moved to Las Vegas and worked a variety of jobs. He worked as an assistant manager at Walmart, a carpenter for a trade show display company, a painter for a casino, and a management analyst to provide housing for mentally ill homeless people. He even tried to start his own business, which “didn’t work out well.” The trade show company even called him back once.

One day he and his wife were checking the MCJROTC website and found a vacancy in an MCJROTC program in Las Vegas. After teaching there, he found out about an opening in Redondo, so he applied for the job and got it.

“When I first started, the program had been under the colonel who had 17 years in, so he’d started to get a little complacent with how he ran the program. The boys had long hair. Kids weren’t wearing the uniform well, belts that weren’t trimmed the proper size, scuffed up shoes. They weren’t wearing the uniforms like the cadets were supposed to wear,” Willoughby said.

When he changed the standards regarding promotions and uniform regulation, a lot of people “bowed out;” however, “bringing the standards up made kids that wanted to be in the program come in, and ones that didn’t want to be in the program leave, so it kind of balanced things out as far as the numbers went.”

Since MCJROTC deals with Marine Corps leadership, Willoughby was able to teach it because he had the knowledge base and experience of being a leader after being in the Marine Corps for twenty years. However, understanding and teaching leadership didn’t necessarily guarantee success.

“The bumps in the roads are when you feel like you’re doing everything you’re supposed to be doing and yet maybe there’s a bad egg in the basket, or there was one year when the entire cadet staff wasn’t really doing anything, so the First Sergeant and I had to make a decision to leave the entire staff and install a new staff halfway through the year,” Willoughby said.

But on that same road is also a lane where students drive forward and grow through MCJROTC.

“That’s probably one of the biggest rewards, being able to see the kids when they start out as freshmen, and they’re really kind of unaware of their own leadership abilities, and to help them increase their levels of leadership over the course of four years, to see how they change and how they can excel and then seeing how many of them have graduated and gone on to have careers in the military,” Willoughby said.

As a class available for grades 9-12, he’s been able to firsthand see students grow and get to know them over a long period of time. According to Willoughby, he’ll miss the cadets and he’ll miss out on seeing their progress, but he’s moving out of the state in order to live somewhere where he can retire and afford to live.

He’ll be taking over as a Senior Naval Science Instructor for an NJROTC program at a school in Savannah, Georgia.

“I will miss Redondo. I will miss the ROTC program. It’s been my life for the past twelve years and I’ve enjoyed every minute of it,” Willoughby said. “I wish there was another way to end my career and go home and not do anything ever again but that’s not the way it all played out.”