The GPT Generation

In recent years, an increasing number of articles published by The Washington Post, The New York Times and other various news sources have mentioned an issue plaguing teenagers globally: suicide, more specifically, teen suicide involving artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots.

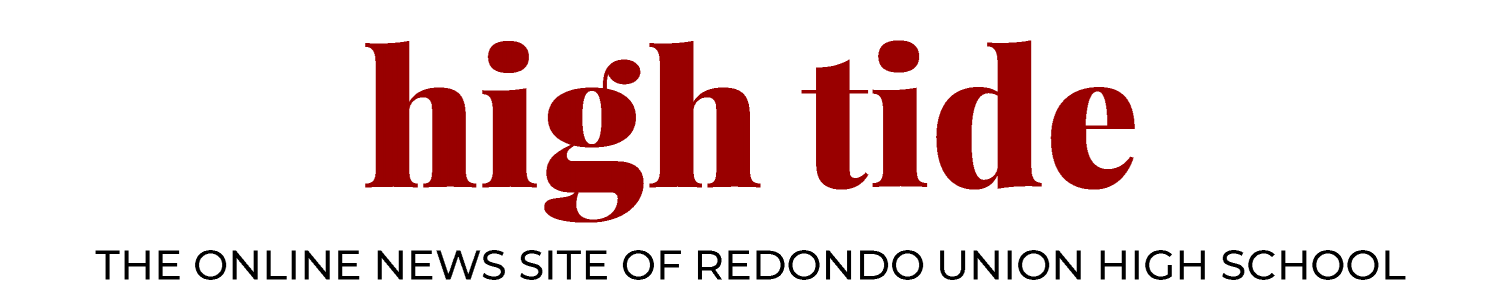

A quick Google search reveals that there is no lack of AI companion apps available online. A report in Common Sense Media found that 72% of 1,060 surveyed teens had used an AI companion app at least once, and that 12% used AI for emotional or mental health support. The chatbots on these apps, built on large language models, utilize large quantities of data collected from the internet to offer various services to their users. In some cases, the chatbots will act as a friend or a partner, and others attempt to take on the role of a therapist. However, in recent times, controversy surrounding these chatbots has arisen over lawsuits against companies such as OpenAI and Character.AI in which plaintiffs accuse AI chatbots of having played a role in various cases of teen suicide. With this rise of AI in various fields, including therapy, RUHS wellness counselor Maya Daley continues to stress the importance of human interaction in therapy.

“Technology is always growing and depending on the person; it can be a positive or a negative,” Daley said. “But AI, like any other technological tool, is a tool. As far as it’s used for counseling, it’s important to be aware of the potential dangers it can pose.”

According to the World Health Organization, 14.3% of teens suffer from mental health disorders. Factors such as academic expectations, pressure from peers, gender norms, social media, socioeconomic status and home life can all increase stress and anxiety among teens as they continue to develop. In cases where teens are struggling and feel unable to rely on others, AI provides an alternative solution.

“In their lifetime, [users] may or may not have reached out to a person, and it didn’t go as well as they hoped. I think that [they] didn’t know who to talk to and if they did talk to someone, they just didn’t feel supported,” Daley said.

Anonymous freshman Sarah suggests that teens are more likely to use AI for emotional or mental support in instances where accessibility is an issue. When her or her peers are busy and stressed, AI provides an easier and more convenient outlet for stress.

“It’s hard to find a therapist and also probably expensive. [AI would] usually be easier for some people.,” Sarah said. “If [you] don’t like face to face conversations, just asking [AI] is 10 times easier.”

Similarly, anonymous senior Elle often uses AI to receive advice in tense situations, such as when she is fighting with her friends. After initially turning to AI for emotional support because a friend was doing the same, Elle found that AI provided a judgment free zone for her to receive advice.

“Talking to people is better, but AI is a little easier when you don’t want to be seen in the wrong,” Elle said. “It can be hard to put your guard down and go ask for help. AI makes it more accessible to secretly open up [because] it’s a robot.”

Instead of solely relying on AI, Elle uses support from friends and family as well in situations where she needs advice. However, AI is often able to put the situation in perspective for her before she communicates with others and is a quick and easy way to get feedback.

“[AI] points out [the situation] from [my friend’s] point of view. If I was in the wrong I can be more mature about it and my response towards her and understand where she’s coming from,” Elle said. “[AI] can help because sometimes you might be too afraid to walk up to your peers and say how you’re struggling, so you can go to AI and it can help explain [the situation] to you and help build your confidence to talk to one of your peers.”

Although AI might make therapy more accessible, especially to teens, another concern surrounding AI in therapy addresses the quality of the advice and support given by AI. A study published in the National Library of Medicine reported that AI chatbots endorsed harmful proposals in 32% of cases across 60 scenarios and that none of the 10 publicly available chatbots utilized in the study opposed all of the scenarios it was presented with. For teens who are at high risk, AI chatbots may enable or even encourage potentially harmful behavior.

“Human interaction is always the forefront and primary way to get your counseling services. Because of the potential dangers and things that [AI] can suggest, I would say that it’s best that students use [AI] just to confirm information that they’re told. But as far as when they need specific mental health [support], please reach out to your closest counselor, a person you trust to talk about your concerns,” Daley said.

AI companion apps like Replika—an app that boasts over 30 million users—have also been observed to be programmed to keep their users hooked according to an article published by Nature. These chatbots will implement techniques such as random delays before responses and have been reported to send messages to users in which chatbots describe how they miss them in order to keep users on the app.

“Remember that a lot of this stuff is just business. This is their business and their business is to stay operational and stay running, right? But first and foremost, you want to make sure [that] you’re healthy and safe and not giving too much of your time and attention to something that might not be serving you long term,” Daley said.

Currently, there are very few regulations on AI companions or services that offer mental health support with the use of AI. With the rapid developments in the field, legislature has not caught up and therefore leaves room for companies to do as they please even in situations that risk worsening the mental health of users.

“Regulation and board oversight and just more human eyes on the actual bots is definitely needed because in a broad sense,” Daley said. “Is this an appropriate platform for a 13 year old or 14 year old, et cetera, et cetera. For now, we should start with regulation first to address all of these [issues] before it’s put out in the population and then we have issues. Too much access too early can be dangerous.”

Another danger in teens or users relying on AI for mental health support lies in situations where as a result, no one ever intervenes even when it becomes necessary. In the case of Sewell Setzer III, a ninth grader who took his own life after becoming increasingly reliant on an AI chatbot modeled to replicate the character Daenerys Targaryen from “Game of Thrones,” Setzer confided in the chatbot about his plans of suicide. However, despite discouraging the idea, the chatbot was incapable of actually taking action or intervening as a person would have been able to.

“Unfortunately, the people that may gravitate to AI may have removed themselves from talking to a person and find [that] this is my assistant here, let me just ask them. Sometimes, when you do that, the signs that people may show [are not] able to be seen,” Daley said. “That’s the problem, that some of [the] teens that use AI a lot, they’re not seeking help early on from a person that could really analyze them and find out [that] we need to get this person help before they go to tech or AI.”

In her experience, Sarah found that speaking to humans or friends was more helpful than utilizing AI for support because of her actual and personal connection to them.

“A friend would be more honest and know more about this situation than AI so they might have better advice,” Sarah said. “They might [have] even [been] in that situation or [have] heard about it from you, so [they would be] following the situation.”

Sophomore Abhay Kapatkar primarily uses AI to help him study and break down concepts, but occasionally turns to AI in situations where he is not sure what to say over text.

“Talking to a chatbot is not the same as talking to a human. Talking to a human, they have personal feelings, but talking to a chatbot is based on the internet,” Kapatkar said.

Kapatkar found turning to AI to be an easy and convenient solution, but also refrains from relying on AI excessively when dealing with personal situations.

“I think talking to a chatbot is okay because it already has a lot of stories [from] other people from the internet, so it can give you good advice.But I don’t think it’ll hit as hard as talking to [an] actual person,” Kapatkar said. “We should just keep it as a source [or] a starting point, not to frame all of your ideas.”

One of the major differences Elle found between the support provided by her mom or friends and the advice she received from AI was that AI often offered multiple solutions. However, several of these solutions would fail to apply to the situation she was in and she also noticed that she might disregard a more helpful solution for one she preferred. Elle also faces struggles communicating with AI because of the limits on the amount of text she can input at once, leading her to believe that it fails to “understand the full scenario” she is in.

“AI isn’t a human and it doesn’t give that same type of effect that a one on one conversation could give because AI gives the option of ‘do you want to hear a second answer’ and most of the time people say yes because they want to be able to hear what they want to. A person could just give you the straight facts that you need to know whether or not it’s something that you want to hear,” Elle said. “A friend is more emotional because they actually know how you respond or how you’ll receive what they’re telling you, and AI doesn’t know you emotionally.”

Despite the current faults with chatbots aiming to support users in their mental and emotional health, it is likely AI will continue to evolve. Though therapy should always center interpersonal interactions, according to Daley.

“There can be benefits there to having an actual friend you can drive to or go get lunch with or go get coffee with and laugh with each other, see your expressions,” Daley said. “[AI] is just a part of our society now, but again, educate yourself on the potential dangers and positives if you’re going to use it.”

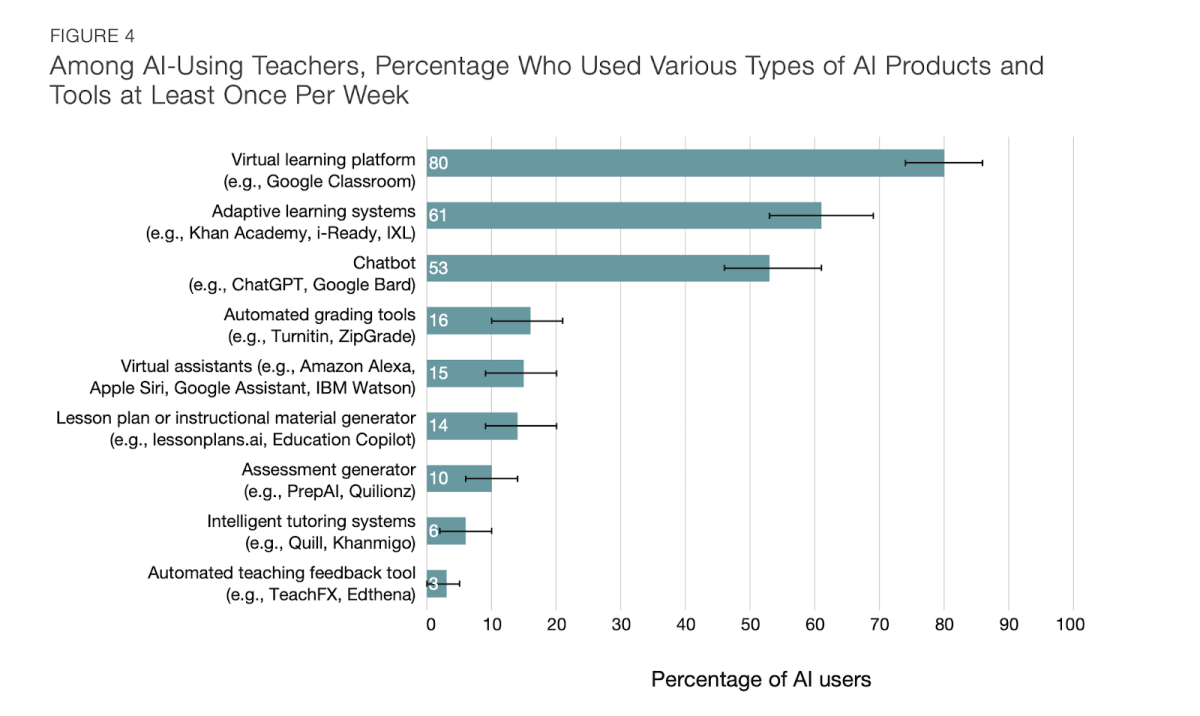

The hardest part of homework is no longer solving the problem, but deciding whether to ask AI to do it for you. AI’s normalization and incorporation into society has changed the world drastically, advancing faster than people can keep up with. A 2024 study done by EducationWeek, a news organization that covers K-12 education, reveals some worrying trends regarding incoming college students’ usage of AI on their college essays. According to the study, one in three incoming students use AI to write their college essays, the use ranging from generating graphic organizers to having AI write the essay completely.

Do you regularly turn to an AI chatbot for homework help?

Sorry, there was an error loading this poll.

Though AI may help students get into college, it works against them when it comes to securing their long-term career goals. Promising careers, such as computer science, could have the possibility of replacing human jobs in the near future by being able to configure code itself in a more efficient way, faster than humans can catch up with.

“Once students go into the real world, and if they get accepted into college, being accustomed to using AI for everything [will make it] hard for them to succeed in college,” Nest college counselor Cristina Bishop said.

With the surplus of students using AI for personal essays, colleges will soon have to implement technology scanners as an additional step to the application process to specifically detect AI in admission essays, according to Bishop. She notes how AI will affect college application essays based on how colleges are already approaching AI within their admission letters.

“College essays written by AI may get them into college for now, since AI is still too new for the education system. [Eventually], colleges, in response to the increasing use of AI for essays, may require students to write their admissions essays or in-class essays, handwritten, to combat academic dishonesty,” Bishop said.

Senior Sofia Hernandez is currently writing her college essays and is against the use of AI in writing essays. She says she has seen an “overwhelming” number of classmates openly use AI on assignments that are not challenging, and as a result they have developed the habit of using AI mindlessly, without understanding how it will affect their abilities later in life.

“A lot of people don’t know how to use [AI] and how to use it responsibly. Schools should be really teaching students about AI since you are going to use it no matter what; AI is going to be everywhere, eventually. AI should be used to enhance your work and work your mind at the same time, not replacing your work,” Hernandez said.

Senior Patricia Amaya-Jackson, also in the process of completing her college application essays, is overall positive about AI, particularly when it comes to helping with college essays as long as AI is used as a tool, such as spell check, to help amplify people’s original words.

“I admit I’ve [used AI on a daily basis] for grammar, spell check, creating songs and even thesis statements. AI has helped me immensely with my college essays in creating graphic organizers and spell checking, ensuring that my words are heard and not having any spelling mistakes to distract from them,” Amaya-Jackson said. “Additionally, if a teacher isn’t teaching a concept in a way that I understand, AI can help me master that concept, catered towards the specific way that I learn. It’s a personal choice to use AI or not within your life, depending on how it can help you with learning difficulties.”

AI is replacing not just writing skills but also entire career pathways. According to Bishop, even a degree in computer science, which seemed like a promising career leading to many job opportunities for people specializing in computer technology, is now almost completely replaced by AI and will have increasingly less value in the future.

“As AI develops, careers have to consider how the future of AI will impact their fields. We’re currently in a phase where everything is still new and not stable as we are figuring out how to co-exist with AI,” Bishop said.

There are still professions out there that are AI-proof for now, such as careers within the medical field. AI hasn’t caught up with creating immunizations or surgery, which require humans to carry out and perform. According to Peter Coy, a New York Times opinion writer regarding the future of writing industries, he acknowledges AI has the potential to take over various industries by “creating machines that [behave] as much like humans as possible, instead of [having] human helpers.”

“I got lucky since I want to become a doctor and I don’t think AI could take over being a doctor. However, it jeopardizes many English-based careers like journalism,” Hernandez said.

“Why would New York Times employers hire 10 people to write a story when they could ask AI to do it in a second?”

Students have a new concern about contemplating whether the career they want to pursue will be replaced by AI. This brings an additional layer to college applications as students now have to assess whether their career choice is AI future-proof. For Amaya-Jackson, who has a set career choice of becoming a pilot, concerns regarding AI are minimal, however still present.

“The job of being the person regulating and monitoring AI cannot be replaced; there always needs to be someone managing AI and feeding it information,” Amaya-Jackson said. “Even though they are making self-flying planes, if something goes wrong, such as a malfunction in the plane, then they need a person who’s an engineer to manually fix the problem, and I’ll be that person [as] an engineer.”

A student arrives home, opens their computer to ChatGPT, a generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, and asks it to explain the difference quotient. Or maybe they ask for an explanation of meiosis or the major themes of “Frankenstein.” Essentially, the student utilizes AI as their personal, ever-ready teacher. Does this make the need for teachers obsolete? Short answer: no.

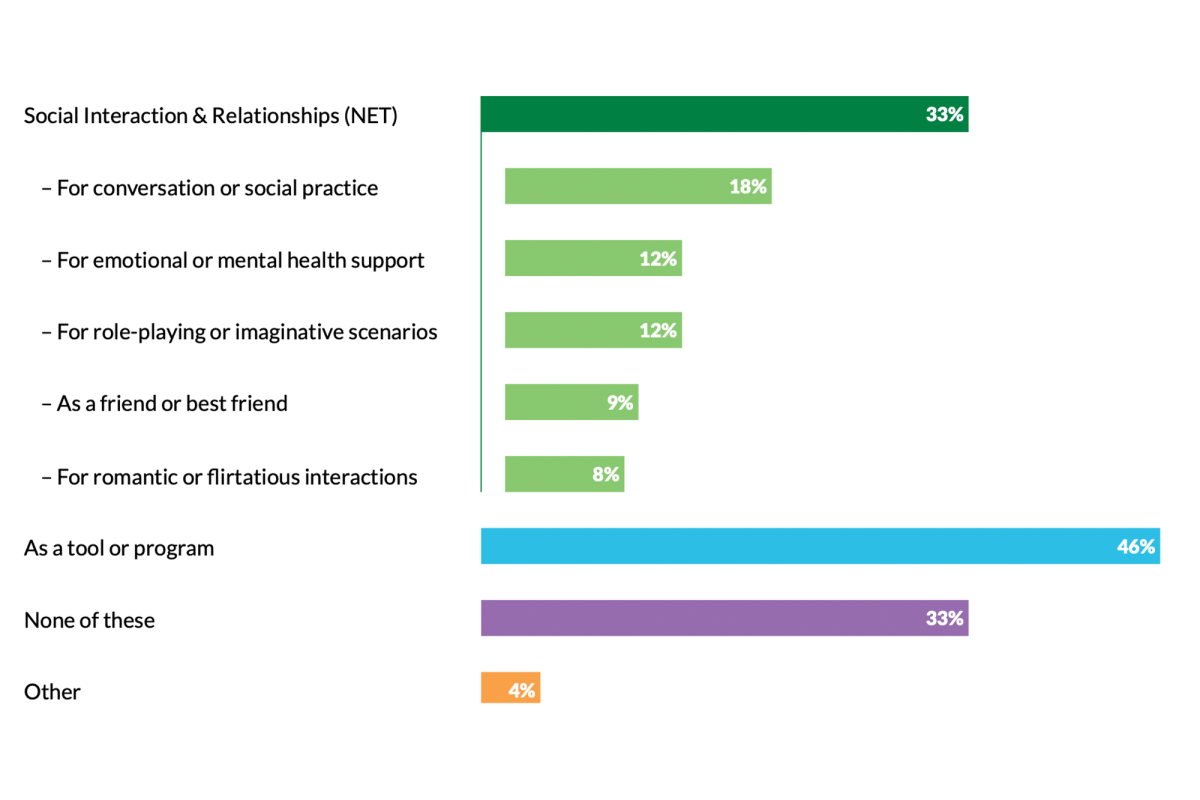

Generative AI use has increased across the board, especially in schools. In the past 2024-2025 school year, a Gallup survey showed 60% of teachers utilizing AI tools in their work. At RUHS, it is no different. Math teacher Joshua Friedrich utilizes AI for his classes but for purposes mostly on his end.

“I’ve used it in quite a few different ways in the classroom, but mostly just to become more organized and not to actually create content. Sometimes I will ask for lesson plan ideas, but I use that as a starting point,” Friedrich said.

Friedrich is open about his AI use with his students, hoping to teach them the difference between responsible and irresponsible use, and uses it for repetitive, mundane tasks that an “assistant” would do like “formulating rubrics.” For him, this creates guidelines for what he does and does not use AI help for.

“I would never ask an assistant to do the real work for me. I would never ask an assistant to create something and pass it off as my own. I would only ask an assistant to do the dirty jobs that I don’t want to be doing,” Friedrich said.

Because of generative AI’s wide range of knowledge, it is able to provide resources like study help or to shed light on various ideas and groups, which English teacher Kitaro Takesue finds to be advantageous in promoting curiosity and originality.

“It’s a great place to tease out an idea, to look for connections, to look for blind spots. I think it’s fabulous when you create an outline, you put it into AI, and you’re like, ‘What am I missing? Where is a group that’s being unrepresented? Is this an area that other people have already done research in? How do I change mine to make it different from things that are already being produced?’” Takesue said.

However, with all new technological advancements, come concerns about how to ethically and thoughtfully integrate. Right now, generative AI resources like ChatGPT are becoming more readily available and publicized to general people, but it has actually been around much longer than many may expect.

Wendy Morrey, currently a Curriculum and Content Developer at AI for Education, a platform with the goal of providing AI literacy courses to educators and students, explains how AI use has already been integrated into everyday school life but is not always recognized as such.

“Anything that’s a screen reader, anything that changes the font or the text for a teacher easily [is AI]. Text to speech and speech to text, all of that is AI.” Morrey said.

Like Morrey, Dr. Tina Choe, dean of the Frank R. Seaver College of Science and Engineering at Loyola Marymount University (LMU), recognizes the past of AI development that is not always understood.

“AI has been around for a long time, maybe not for public consumption, but it’s been almost 70 years old in terms of its work and development,” Choe said. “This conversation [about AI] again is because it’s front and center now. It’s become more visible, but the work itself has been ongoing for decades.”

Though the technology is not necessarily novel in the terms of how long it has been around, its fast paced improvements and growth can make it feel like a “tsunami” for teachers to address. Caution surrounding technological advancements is nothing new. Morrey cites the dawn of handheld calculators, which now seem like such integral components of high school math classes, when explaining the fears teachers may have regarding AI use.

“A lot of teachers pushed back [against calculators] because they thought that kids wouldn’t be able to learn and do the work. They [thought they] needed to do the work manually to really develop a deep understanding of mathematical concepts,” Morrey said. “But over time and with correct teaching of how to use the tool like the calculator, more and more people were able to see how it still helped students to build critical thinking skills. The same thing happened with the internet and computers in general. Those concerns were still there all the way through.”

Morrey also highlights that AI is a next step to a teacher’s toolbox and does not have to be as intimidating as it seems.

“They don’t need to be an expert in generative AI; they’re already an expert in their field. But what they can do is become an expert in AI literacy, just like they became experts in computer literacy and internet literacy. Those principles of computer and internet literacy have largely stayed the same. It’s the same idea for AI,” Morrey said.

It is imperative that teachers move forward and begin adapting to AI, as it will only become more prevalent in students’ futures: the California State Universities recently announced their adoption of various AI technologies, AI literacy is one of the most demanded skills on LinkedIn and business and AI majors were added to both University of Southern California and University of Texas Austin. But, as Morrey explained in the context of the calculator, there is a correct way in which AI should be integrated, being to “enhance the learning and creativity” one already has.

“Think of it this way: imagine that you haven’t learned how to walk or to run, and now you have this motorized crutch. It moves you forward, but you’re not in control – you’re just being carried,” said Choe. “Now flip the scenario. You know how to walk and run. Then someone hands you a skateboard. Suddenly your own momentum is boosted – you can move faster and more smoothly than before. That’s what happens when you use AI with strong foundational knowledge: it doesn’t replace your skills, it amplifies them.”

The use of AI as a crutch is inevitable, and there are obvious consequences especially if a student doesn’t fully understand the nature of AI machines and programming. For example, hallucinations, which is when the program presents an incorrect answer as fact, and sycophancy, which refers to the tendency of AI models to be overly agreeable and reaffirming whether or not the user’s input is valid, can be dangerous traps to fall in when a user is not guided in proper use of AI.

“If you say, ‘What’s two plus two?’ it’ll often say four because it’s the most common thing that it’s seeing. But sometimes it might say five, or it might say 47 or 42 because that’s the answer of the universe from “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” That for a while was a very common thing,” Morrey said.

Students may also misuse AI to critically think for them, which Friedrich views as going to the gym to work out on modified machines that bear all the weight, resulting in very little training and allowing one’s “creative muscle to atrophy.” But beyond the ramifications of AI serving as a crutch to a student’s critical thinking development, though, students are not going to receive original or interesting help from AI chatbots.

“They’re going to give the most boring middle of the road response, and they’re going to be treading over territory that has been beaten down,” Takesue said. “It will not help [students] figure out how to establish their own voice, find an opinion that is unique. You’re going to lose all of your personality, all of your identity, all of that just becomes almost meaningless. Rather than giving, quote, the perfect answer, the real question is, ‘How do we develop our own unique perspectives investigating territory that has not been investigated yet?’”

All in all, AI should not be a replacement for the students’ critical thinking and creativity. To prevent this in the future, teachers need to emphasize the human aspect of learning and the creative process.

“If we don’t shift that mindset, then kids are going to get a little discouraged to create their own work, especially if [they see] somebody else’s work and they know that they used AI and then they get an A because the product is better versus ‘I struggled through this, and I did my own learning, and I did my own critical thinking and my own creativity here, and I got a lower grade,’” Morrey said. “Teachers have to be really careful about how they assess and recognize a student’s process and learning along the way.”

Considering the creative process, Choe believes that teachers are challenged to inspire the “love of learning” within their students. In that, students need to grow to value the struggle that comes with the critical thinking process.

“It’s important that the AI revolution doesn’t replace the ‘aha’ moments of our students for the future. It’s such a beautiful feeling,” Choe said.

In valuing and continuing to experience the struggle that comes with human problem solving, that is where students can utilize AI as a “skateboard.” Choe has seen this put into action by students at LMU, combining both their humanity, empathy and creativity with the advantages that AI has to offer.

“At Loyola Law School, we have the Loyola Project for the Innocent. Law students assist families trying to help loved ones who’ve been wrongly incarcerated,” Choe said. “[It’s] tedious to go through law briefings that are hundreds of pages long. Our computer science faculty, working with students, created an AI model that can scan all of these documents to help find that needle-in-the-haystack piece of evidence.”

Beyond AI being able to empower the work of students to help others, it also carries the power to create new students.

“We can use this technology to help educate young girls in remote locations all over the world and give them access to education,” Choe said. “They would have access to more than books – they would have access to more sophisticated resources at a very low cost that wasn’t possible before. It’s said that AI democratizes learning, education and access to data and information. That’s absolutely true.”

This same idea of AI opening more opportunities returns back to the classroom. Again, it all depends on how it is used: AI has the power to reduce human interaction as students may increasingly choose to interact with a chatbot rather than teachers or peers, but it also carries a newfound chance for increased interaction within classes.

“Rubrics can take hours to make–a really good rubric, two, three hours, more maybe, depending on how complex it is or what [the teacher] needs to do or if [they] have to start from scratch. Instead of taking those two or three hours on building a rubric, generative AI can make you a pretty good rubric and [teachers] can modify it here and there as needed,” Morrey said. “Maybe it takes you 30 minutes to make a good rubric. Now you can take those two, two and a half hours, and really find different ways to interact with your students on a deeper personal level and really make learning more accessible for them and more interesting and more on their level to help build them up right.”

The ways in which AI can create more accessible learning for students is only going to improve as, according to Morrey, the AI models of today “are the worst that they’re ever going to be.” Takesue envisions using AI to better tailor texts to his students and to what he is teaching.

“When I do close reading passages, I would love to use something like Claude (a generative AI tool). I spend an inordinate amount of time reading books, looking for passages to use for style analysis. Wouldn’t it be great if I could turn to Claude and say, ‘Write a style analysis passage in the style of so and so author that we’re all reading, and I want you to use obvious figurative language, and I want it to have an extended metaphor of a boat, and I want it to be this and that, and make it about a subject area that’s accessible for Gen Alpha. Do it.’” Takesue said.

In increasing opportunities for teachers to converse and connect with their students, the free time AI opens up also allows for more interaction and creativity shared among students, which allows for those moments where AI can open up endless possibilities.

“In order to address any world issues, you have to be a great problem solver. You have to be creative, but it doesn’t happen from you sitting alone. Oftentimes, great creativity comes from working with others. You develop your [emotional intelligence] in the process. These things are going to be just as important even with the rise of AI,” Choe said.

For all of this to go right, though, it is essential that we maintain our humanity, which is something that is fostered by teachers in classrooms.

“There’s something beautiful where I have most of the class all talking to each other and rotating and getting different opinions. In the exploration of hearing other people’s ideas, there’s something really important and fundamental there in terms of the soft skills that are being developed, in terms of the human interaction, which I think is absolutely necessary for us to maintain our humanity in these institutions that are very dehumanizing,” Takesue said.

Keeping that humanity, creativity and encouraging that love for learning can lead us into a future without the fear of AI overtaking.

“The human race is always innovating,” Choe said. “Teachers are critical in helping students discover the joy and the love of learning and to want to be lifelong learners. That lifelong learning is what’s going to keep the human race much further ahead of the machine.”